I’m Younger Than That Now

In three years of high school, Chatsworth High class of 1974, I took five Advanced Placement classes and did well in all of them. But I only took three of the AP tests. Passing the test could be worth college credits. I didn’t want too many of those, because I believed folklore claiming that college would be the best time of my life. I wanted the full, four year experience. What overconfidence! As it turned out, I just barely graduated from college, having to take an extra quarter to earn sufficient credits. I was eager to be out of college. I almost decided that it would not be worth the time and expense, but in the end, I qualified for and received my diploma.

One of the AP classes I took but did not seek college credit for was English (Lit or Comp, I know longer remember, but we did both read and write). I asked a friend who took the test what the essay subject was. He said it was to describe a stressful situation and how you reacted to it. What stressful situation did he write about? The stressful situation of writing an essay for an AP English exam!

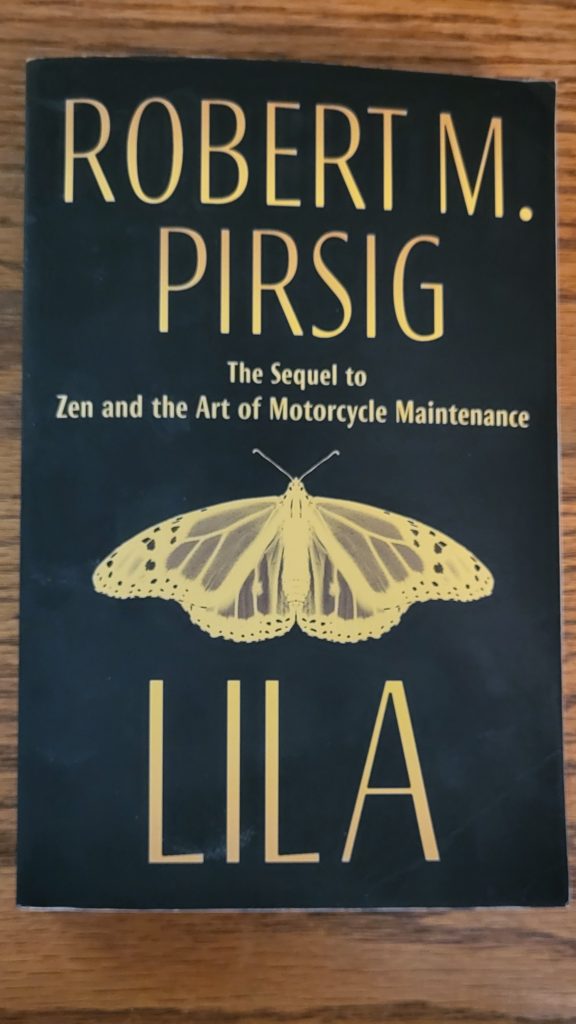

I am reminded of this as I read Lila, An Inquiry into Morals, the sequel to Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert M. Pirsig. I wrote about reading the first book in I Was So Much Older Then. In 1991, seventeen years after publishing one of the best-selling nonfiction books ever, Pirsig published the sequel. In 2022, I finally read it. To me, it seems he adopted a similar device to my high school friend’s approach to the AP exam essay. A lot of the book seems to be taken up with anecdotes from Pirsig’s life since publication of the first book, and with his techniques, strategies, and personal philosophical confessions and epiphanies that become the second book, the one we are reading.

There is a brief passage in which Pirsig, in his persona of Phaedrus, somewhat grudgingly admits that eating vegetarian is slightly more moral, in his system, than eating animals. That position is grounded in his idea that higher degrees of evolution confer higher morality. He has fixed ideas of a scale of evolution, among living creatures and among values inorganic, biological, social, and intellectual. However, no character in the book eats vegetarian, and the matter is dropped, never to be mentioned again.

Pirsig strikes me as an honest reporter, certainly unsparing of himself. The book is full of ideas. He tells an authentic-seeming anecdote about making a commitment to Robert Redford about movie rights, and then deciding to renege. Also interesting to me is the discussion of insanity and psychiatry, based on the author’s personal experience.

To Phaedrus, his Metaphysics of Quality explains a plethora of philosophical conundrums, from free will versus determinism, to rising crime rates, to racism. To me, it explains too much. It is like explaining all questions as gods’ will. He dislikes religion, but embraces the right, Dynamic, kinds of mysticism. Uses the word “patterns” to mean several different things, lending vagueness. I don’t see how one could adopt his morality as a means of knowing what to do in difficult situations.

Here is a passage I find baffling:

We must understand that when a society undermines intellectual freedom for its own purposes it is absolutely morally bad, but when it represses biological freedom for its own purposes it is absolutely morally good. These moral bads and goods are not just “customs”. They are as real as rocks and trees.

Pirsig berates most philosophy as “philosophology,” which he says relates to philosophy as art history relates to art. He takes pride in doing original philosophy, but mentions only William James as a modern philosopher who qualifies for the title.

I don’t think there is much morality to learn from this “inquiry into morals.” Pirsig seems to be mistaking his emotional reactions for morals, and then creating justifications within his Metaphysics of Quality. None of the characters strike me as shining examples of, well, character. There are hard moral questions, but they are not addressed here. By contrast, it’s easy to see that breaking unforced commitments is wrong. Failing to act in a way you have determined to be morally superior is wrong.