That Reminds Me

There you are, minding your own business. Something you hear, read, smell, see, taste, or just think about suddenly calls to mind something else, seemingly unrelated, that you haven’t thought about in years. The recalled event or situation may only have the most abstract or tenuous connection to the triggering stimulus.

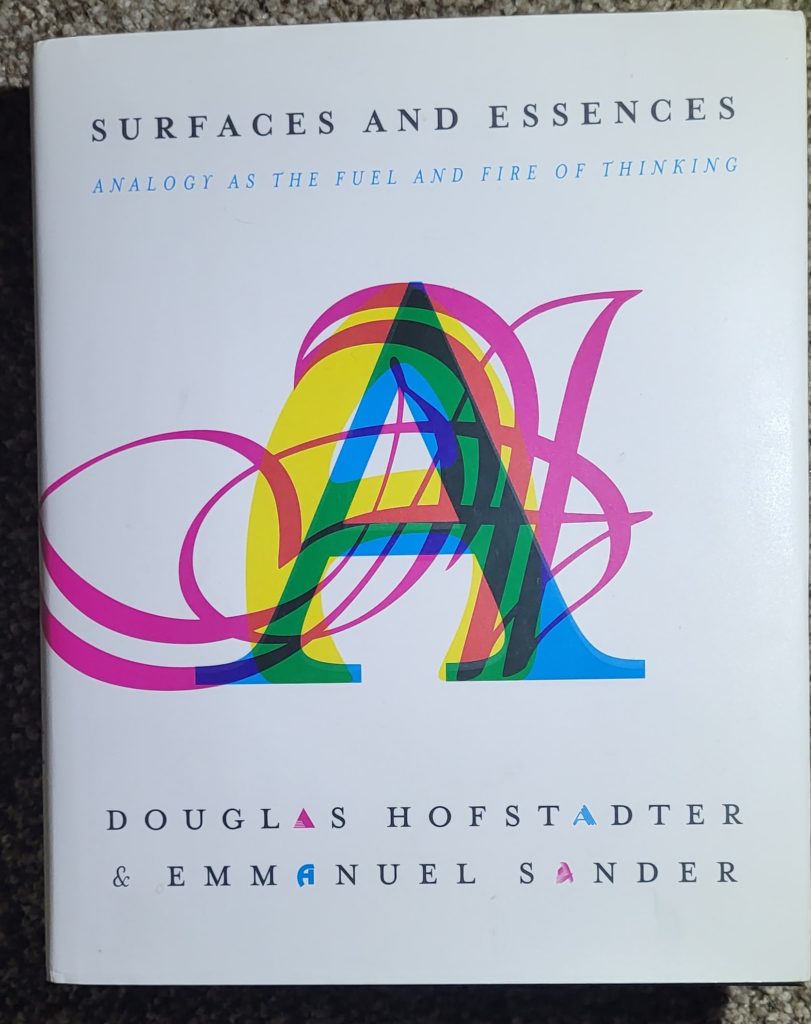

Surfaces and Essences, Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking, by Douglas Hofstadter and Emmanuel Sander, addresses such remindings and many other common experiences, such as word choice errors and eureka moments, within the thesis named in the title.

Simply, the thesis is that all thought is based on analogies. This includes creating concepts by combining or differentiating existing concepts. It includes recognizing common objects as members of categories such as “chair” or “drinking glass.” Also, when we add situations (i.e. memories) to existing categories (e.g. “times when I thought I was wrong, and I was”). When we find in memory matches for a situation at various levels of abstraction. For example, is this a “took a chance and got lucky” situation, or maybe a “genius is mostly preparation” situation? Creating new categories for novel situations is really making analogies.

Hofstadter and Sander wrote the book collaboratively in English and French at the same time, a novel way to address difficult translation issues. Early in the book, they go to great lengths to distinguish mental categories from the words we use to denote them. This is important and difficult, because not all concepts have preassigned words, though many do. And words are all we have to communicate abstract ideas about both words and concepts. Language is chock full of words and expressions which originated in metaphorical analogies that have since been lost. For example, what does “chock full” really mean? There are hundreds of other examples in the book, which full of word play. They deliberately use well-worn cliches throughout, to demonstrate how we effortlessly understand them without ever taking them literally.

Superficial or obvious analogies are easier to trigger than deeper, more subtle ones. This is confirmed by many psychology studies. However, the design of the studies, the source-target paradigm, is itself analogous (per the authors) to “medication that is effective but that has serious side effects,” which have “unfortunately helped to propagate misleading ideas about analogy making.” The analogies we study are very different from the analogies we think in, both the superficial and the deep ones. The experiments give the subjects limited knowledge about a source problem and ask them to analogize to a target problem. In real life, we generally have deeper knowledge to which to analogize a novel situation. We aren’t really that superficial, except in the artificial circumstances of a psychological experiment.

Not just commonplace thinking is analogizing. Brilliant strokes of mathematical and scientific genius are seen as finding analogies between a situation needing explanation and a simpler one that is well understood.

The book closes with a dialog designed to convince the reader that drawing analogies and making categorizations are the same thing. It does well at this, but why is it the conclusion. This only seems to be justified by the tacit assumption that if analogies are not the stuff of thought, then categorization must be.

This book does not delve into how analogies are implemented in our brains. This is a weakness from the point of view that the thesis makes a general statement about all thinking. It may be a strength from the point of view of approaching the problem of creating thought in machines or software.