Why Do We Call Meat “Protein?”

I enjoy watching shows about wilderness survival, like Naked and Afraid, even though I consider the people who voluntarily put themselves in those positions to be crazy. I could never do that. I can’t even walk barefoot on the beach. In the show, the survivalists have to build shelter, make fire, boil water, and hunt, fish, or forage for food. They usually refer to any animal food as “protein.”

I go to restaurants where a dish may be ordered with a variety of meats (chicken, beef, pork, shrimp, fish) or fake meats or soy-based foods like tofu or tempeh. We watch chef competition shows. Here, too, the animal option, or any plant-based substitute for it, is almost always referred to as “protein.”

Meat gets half of its calories from fat. So does tofu. So do fake meats like Impossible Burger and Beyond Meat burgers. Pistachios and other nuts get most of their calories from fat. They are good sources of protein, but they are not protein. Calling them protein makes most of us value them more, because we have learned, incorrectly, that protein, especially animal protein, is the highest valued nutrient we can eat. It also makes it easier to ignore, or justify, the pain we inflict on conscious beings, individual cows, chickens, pigs, and fish, in order to obtain their flesh, eggs, and milk for our food.

We don’t eat nutrients per se. We eat food. Food contains a variety of nutrients, as well as ancillary components which may be beneficial or harmful. Most people get far too much protein. Whole vegetables, beans, and grains have enough protein to meet our needs, provided we eat enough food to fuel our energy needs. Only fruit has no protein, but whole fruits are great food, supplying important nutrition.

T. Colin Campbell, PhD, is the author of two of the best books on whole food, plant-based nutrition, The China Study, and Whole. He has now summarized his personal journey and his case for WFPB in The Future of Nutrition. I have just finished the audiobook version.

Campbell advocates unabashedly for WFPB eating. Instead of picking a single dietary villain, such as saturated fat, sugar, or salt, we should eat a variety of plant foods, as close to their whole state as possible. Parts of the book actually sound like a defense of saturated fats. Parts sound like a condemnation of animal protein as the specific culprit in chronic diseases. We must remember that reductionist science may often conflate effects of saturated fats, cholesterol, and animal protein, since they generally coexist in the same foods. Campbell risks confusion on this point, in my opinion, since he is trying so hard to overcome our preexisting conviction that animal protein is good nutrition.

Another word we often misuse is malnutrition. We use it to mean not getting enough food. It should also include the more common situation, eating food that promotes disease. This table from The Future of Nutrition shows that our leading causes of death are mostly caused by malnutrition.

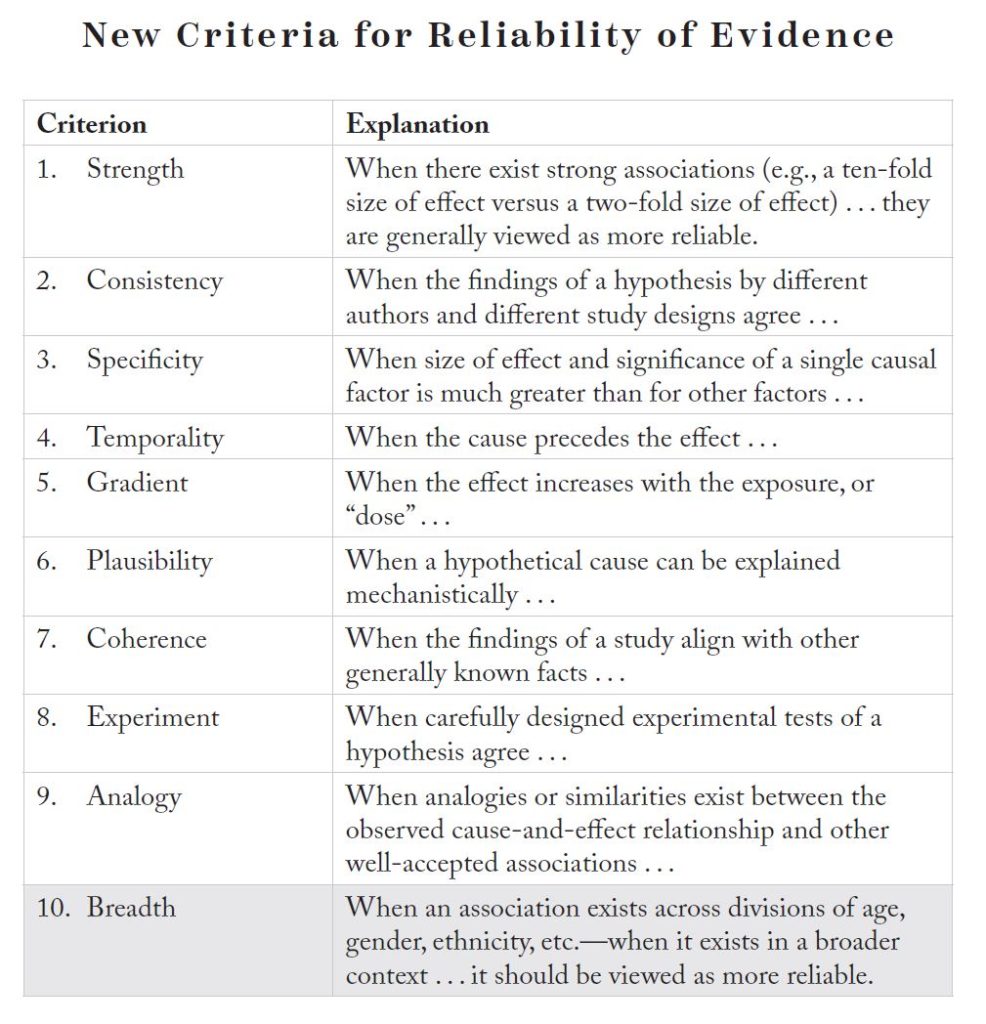

Dr. Campbell argues convincingly that the scientific criteria we revere for testing pharmaceuticals, such as placebo-controlled, double-blinded, interventional trials over a long time period, are not appropriate or practical for testing WFPB eating. He lists the nine criteria we use to evaluate science evidence, and adds the tenth, Breadth. We should not abandon reductionist science, but neither should we ignore abundant evidence for WFPB eating.

The discussion of institutions such as the American Cancer Society and the National Institutions for Health provide important warnings about how incorrect approaches and conclusions can become so entrenched as to be unassailable. Science seen through these narrow filters ceases to be free intellectual inquiry. We must question their authority, but not use that as a reason to distrust all such institutions and disregard all of their findings. Everyone needs to trust someone, but no one can be trusted fully. Our own best judgement is still required.

The last chapter provides Dr. Campbell’s recommendations for how we can fix our broken systems of health care and scientific research. These sound great. Let’s give doctors complete training in nutrition. Let’s fund studies comparing WFPB eating to other dietary approaches over the long term for prevention and treatment of all major diseases. Let’s remove corporate and industry influence over national dietary recommendations, school food, and advertising.

Unfortunately, Dr. Campbell does not explain how we can achieve these improvements. Personally, I don’t think we can. We can take control over our own nutrition, so we should. We can pass this information along, as I’m doing here.